Monday, June 14, 2010

Saturday, June 5, 2010

Saturday, May 15, 2010

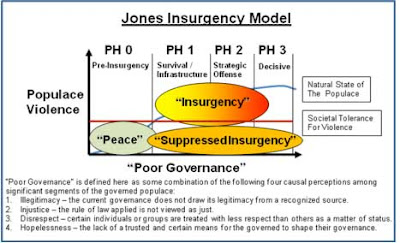

The Jones Insurgency Model

Offered here is the simple proposition that insurgency happens when governance fails. Similarly, foreign terrorism happens when one supports these same failed systems.

• Not the kind of failed governance that draws so much attention to countries like Somalia; which is probably more accurately described as a rejection of forced western, Westphalian constructs of governance for forms more acceptable to their culture and society.

• Not the kind of failed governance that draws so much attention to countries like Liberia; where auspices of statehood are perverted to criminal purposes.

No, the failures that lead to insurgency are far more fundamental, and often so insidious that they are not even recognized or acknowledged by their equally failing leaders; even when pointed out to them, often quite violently, by their own populaces. What makes countering such insurgent causation even more complicated is that these failures do not even have to be real; all that is required is that some key segment of the populace reasonably believes them to be true. The irony is not that this happens in countries like those described above, but that it also afflicts the most developed, upright, and law abiding countries as well. This is the paradox. This is why counterinsurgency is so difficult: it can happen anywhere, its causation is rooted in perceptions of governmental failure; and its resolution is rooted in governmental recognition and resolution of those same perceptions.

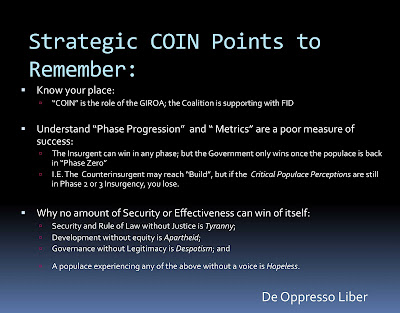

• Security and Rule of Law without Justice is Tyranny;

• Development without equity is Apartheid;

• Governance without Legitimacy is Despotism; and

• A populace experiencing any of the above without a voice is Hopeless.

The above model is a compilation of years of engagement and professional study, primarily at the Operational and Strategic levels, on insurgency and the many manifestations and surrounding effects falling under an ever increasing number of headings and definitions. Subversion, Insurgency, Counterinsurgency, Terrorism, Counterterrorism, Irregular Warfare, Foreign Internal Defense, Unconventional Warfare, Revolution, Dissidence, Internal Defense and Development, Security Force Assistance, and many others, are all related to some extent and touch in varying degrees this paradox of insurgency.

So what does the Jones Model tell us?

As conditions of Poor Governance increase, so does the natural tendency of the populace to act out violently against that governance. The curve running from the lower left corner up and to the right roughly plots this track. While each populace/governance dynamic creates its own unique snapshot of this model, one could also in more general terms plot the status of every populace/governance dynamic around the globe on a single model. Most would plot in the lower left quadrant of “peace.” Those with active insurgencies, such as Afghanistan, would plot up in the “insurgency” zone. Others, where conditions of Poor Governance exist, but the where the natural state of the populace’s reaction to that Poor Governance is suppressed, such as perhaps Iran or North Korea, would plot in the “suppressed insurgency” zone (“perhaps” because media and political assessments from outside sources are a poor measure of a populaces perceptions of its own governance).

Every populace also has its own cultural tolerance for violence. Beginning with Mao’s three phases of insurgency as a widely accepted standard baseline for understanding what stage an insurgency is in, it is the nexus of where “Populace Violence” exceeds “Societal Tolerance for Violence” that conditions leave the realm of subversion/pre-insurgency and enter into what is classically understood as “insurgency.” It is important to understand that the insurgent may prevail in any of the four phases, but success for governance is only achieved by keeping the populace in phase zero.

How does understanding the Jones Model help prevent or resolve insurgency?

The Jones Model implies clear roles and responsibilities. It is the duty of civil governance to maintain the peace internal to a society. Understanding what leads to violence is critical to ensuring efforts are focused on the right areas for maximum effect. Similarly, programs that may seem logical on their face but that are not likely to positively influence the causal perceptions can be identified and either assigned a lower priority or avoided altogether. The Jones Model also places the full onus for an insurgent populace on the governance of that populace. Governmental responsibility is critical for effective COIN. The Jones Model clarifies the role of security forces as well. To merely attack the violence without concurrently addressing the conditions of poor governance may well suppress an insurgency, but is not likely to resolve it. The role of the military should be to supplement civilian security forces, and be employed only when the situation has exceeded civilian capacity. This extra capacity is to create space for civil leadership to identify and address the factors leading to the perceptions of poor governance, moving the populace down, and to the left into “Peace.”

The Jones Model provides for simple, effective metrics. Complex objective metrics may be very precise, but at the same time sadly inaccurate in terms of providing understanding of the state of insurgency within a given populace. Perceptions toward the four causal factors however, are easily gathered through polling and can then be plotted by color coding areas on a map according to phases 0 through 3 as Green, Amber, Red and Black. This is perhaps the best way for the Coalition Forces in Afghanistan to clearly explain to a global audience the current state of the insurgency there now, and also to demonstrate how conditions progress over the course of the next several months as the surge of forces implements General McChrystal’s Population-Centric strategy. Each “focus district”1 could be assessed a color, and reassessed quarterly. This elegantly simple tool works for briefing generals, presidents, or your average concerned citizen, and is arguably far more material and accurate than any of the complex models currently in use.

Lastly, the Model enables an understanding that insurgency is more accurately a civil emergency than it is a war. Waging war against one’s own populace is sometimes necessary, but never good. All violence, however, is not war. By seeing insurgency as a naturally occurring civil emergency resulting from perceptions of Poor Governance, one is far more likely to apply the military in a properly constrained, subordinate role. One is also far more likely to hold civil leadership accountable for their failures, and focus on resolving the conditions and perceptions giving rise to the insurgency rather than simply focusing on the physical and moral defeat of those who dare to stand up to Poor Governance.

Legitimacy is also the causal perception that appears to be the critical link to acts of foreign terrorism. Many well established competing theories dominate thinking on this topic, rooted in ideology, religion, hate, fear and jealousy; all surely contribute, but none of those really stand up to analysis rooted in an understanding of Insurgency. Sixty years of Cold War engagement and a pair of recent regime change operations have all served to cast a cloud of U.S.-based legitimacy over many governments across the Middle East. Populaces who perceive their governance to draw its legitimacy more from the U.S. than it does from the traditional sources recognized by them are apt to commit local acts of insurgency, coupled with distributed attacks to break the ties to that corrupting outside source of legitimacy.

Bin Laden and Al Qaeda have focused on this dynamic from the outset, labeling these failed governments as “apostate” and urging the populaces of these states to rise up against those failed governments as well as against the U.S. and other western powers.2 The religious overtones are obvious, but the undertones are rooted in terms of the Illegitimacy of the rulers of states like Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Yemen and Egypt; and in terms of Western disrespect for the populaces of the region. The injustices of the legal systems in these countries are well documented, as is the hopelessness of populaces unable to influence governance through peaceful means. Looked at through a lens of religion and hate, one can easily draw conclusions of causation in those factors. Looking at the same facts through a lens of insurgency as captured in the Jones Model and the critical causal perceptions of Legitimacy, Injustice, Disrespect and Hopelessness stand out as well. After eight years it may be time for a fresh approach.

Joining forces with these allied governments to attack the insurgent elements of their populaces under the guise of counterterrorism is to attack the symptoms of the true problem, and actually contributes to making the perceptions of Poor Governance worse. Arguably the quicker path to success lies in changing the nature of the U.S. engagement with these governments so as to mitigate perceptions of U.S. legitimacy overriding the will of the governed. President Obama’s instincts are sound; the U.S. must urge and enable these same governments to address the perceptions of injustice, disrespect and hopelessness among their people.3 As Samuel P. Huntington observed in The Third Wave:

"Oil revenues accrue to the state: they therefore increase the power of the state bureaucracy and, because they reduce or eliminate the need for taxation, they also reduce the need for the government to solicit the acquiescence of its subjects to taxation. The lower the level of taxation, the less reason for publics to demand representation. “No taxation without representation” as a political demand; “no representation without taxation” is a political reality."4

Some day this last quip may be as notoriously famous as Marie Antoinette’s retort of “Let them eat cake!”

So, applying the Jones Model to the greatest security challenges facing the U.S. today suggests a deceptively simple, yet potentially powerful change of approach to foreign policy. First is to assess every nation with which the U.S. engages for how the major groupings within their populace perceive their own governance in terms of Legitimacy, Justice, Respect and Hope. Second is to ensure that the form of U.S. engagement is designed so as to be least likely to create perceptions of preemption of Legitimacy by the U.S. (remembering that this is as viewed through the eyes of those populaces; need only be perception and not fact; and that the perception of U.S. policy makers as to the intent and nature of said engagement is completely immaterial). Lastly is to encourage Hope; to tell the people of the world not to despair, while at the same time applying carrots and sticks as required to the governments of the same to engage their populaces and to make reasonable accommodations on terms acceptable within their unique cultures, to give the people a legal means to voice their concerns. Just as the word “Democracy” does not exist in the U.S. Declaration of Independence or Constitution, it should be absent from this engagement as well. Self-Determination is the path to Good Governance.

At the end of this month, President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan is scheduled to conduct a grand “Consultative Peace Jirga.” His quest is an existential one; it is a quest for Legitimacy.

In the weeks leading up to this Jirga, Mr. Karzai has famously made cutting remarks aimed at the Coalition in general and the U.S. in particular. He has also reached out to leaders of opposition organizations and to the heads of states in greatest opposition to the policies of the U.S. and the West. He knows he must create a sense of separation from those who placed him in office. President Karzai understands that the strategic key to stability in Afghanistan lies not in the surge of Coalition Forces, nor in the major military operations in Helmand and Kandahar provinces. These are essential supporting operations; but Mr. Karzai understands that his presidency presides under a cloud of Illegitimacy and that foreign armies fighting to preserve his office can do no more than suppress the violence for some short time. He must show his people respect and provide hope to those segments of Afghan society currently excluded from participation in governance and opportunity.

No model is perfect, and the Jones Model is no exception to that rule. This model has existed in various forms in the author’s head and on paper for several years, and will likely look slightly different in the future than it does as captured here today. There are many voices and opinions, both modern and historic, competing for space in today’s marketplace of ideas on this topic. Many have contributed to the understanding captured here.

De Oppresso Liber.

[1] General McChrystal identified a number of “focus districts,” where COIN effects are most critical in the coming months for success in Afghanistan.

[2] FBIS Report, Compilation of Usama Bin Laden Statements 1994-January 2004 ; http://www.fas.org/irp/world/para/ubl-fbis.pdf[3] Larry Diamond, “Why Are There No Arab Democracies”?, Journal of Democracy, January 2010, Volume 21, Number 1.

[4] Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 65.

Monday, May 10, 2010

Is President Obama's Afghanistan strategy working?

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/05/07/AR2010050704506.html

Topic A

Sunday, May 9, 2010

With Afghan President Hamid Karzai visiting Washington this week, The Post asked experts whether the surge in Afghanistan was working. Below are contributions from Erin M. Simpson, Gilles Dorronsoro, Kurt Volker, John Nagl, Thomas H. Johnson and Andrew J. Bacevich.

ERIN M. SIMPSON

Member of the Afghan International Security Assistance Force's Counterinsurgency Advisory and Assistance Team; spent the past several months in southern Afghanistan; the views expressed are her own

Any discussion of the effectiveness of the surge must begin with two observations. First, counterinsurgency is an exercise in competitive governance, meaning the troops "surged" to Afghanistan are only part of a very complex equation. Second, less than half the troops that President Obama authorized in December have arrived here. It's far too early to tell whether the so-called surge has "worked."

Most of the troops who have arrived are Marine battalions deployed to Helmand province, with many participating in coalition operations in Marja -- in many ways the hardest test-case of Gen. Stanley McChrystal's strategy. After tough fighting, we see initial, fragile signs of progress. Marja has shifted from being under 100 percent Taliban control, with no Afghan officials, to ever-increasing government presence. Twenty Afghan officials work there and are starting to bring basic services to long-neglected Afghans. Elsewhere in Helmand, Marines have moved into the "hold" and "build" phases of their campaign -- especially in Nawa and Garmsir, where many senior government and tribal officials have returned to work after violence drove them into "exile" in the provincial capital.

For the "surge" to succeed, coalition and Afghan officials will need to capitalize on this change in momentum in Helmand. This includes maintaining government effectiveness through the critical fall planting season, providing the assistance necessary to allow farmers to plant winter wheat instead of pernicious poppy. But the Taliban won't win by outfighting the coalition; it can win only by outgoverning the Afghans. The early phase of the surge is getting Afghans back into the governance game. This is where we must focus our attention.

Sunday, April 18, 2010

He which hath no stomach for this fight, let him depart

On a recent visit to Orgun-E to visit 3 Geronimo – the Battalion Task Force assigned to that particular sector in Paktika – I came across a quote from Shakespeare that I have long favored.

“He which hath no stomach for this fight, let him depart.”

The phrase was uttered by Henry V as he rallied his soldiers on the morning of the battle of Agincourt. Outnumbered by his enemy 10 to 1, he asked his men to fight for honor, king and country – but asked that those who did not want to fight to depart, saying that he would not want to share the glory with those who would not risk all to fight with their king.

The phrase seems equally accurate here, but for entirely different reasons.

Counterinsurgency is a war of patience, persistence, presence, and restraint (dare I coin “P3R?” No – I will not do that to you…). It is less about direct combat with the insurgent than it is about building the capacity of the host nation to fight - and to develop their economy and establish good governance under the rule of law.

Hard to explain to an Infantry NCO whose job description reads something like, “responsible for the conduct of combat operations, to include raids, ambushes, and movement to contact.”

Or a 2nd Lieutenant who joined the Army to “close with and destroy the enemy by…”

You get the point.

And yet we must ask our warriors adapt to this environment and to this fight. They must enable their Afghan partners so that they can take the fight to the enemy. And they must concern themselves with governance, development, and information ops – all while providing the security needed to protect the population.

This challenging mission set has resulted in some pretty restrictive Rules of Engagement – and as a result, more risk to our Coalition Forces.

But to succeed in this endeavor, we must change our mindset, broaden our approach, and accept greater risk.

To summarize: we must fight this war according to the proven principles of counterinsurgency and the tactics, techniques and procedures divined over the last few years of this war.

Those who cannot adapt put this entire venture at risk. And thus I say:

“He which hath no stomach for this fight, let him depart.”

*Roger Carstens is a retired career special forces officer, former special operations fellow at the Center for New American Security, and currently serving in Afghanistan as a Counterinsurgency Advisory and Assistance Team Leader in RC East.